Continuing our look at the changing times of baseball, let’s look at some traditions in baseball that have already changed- for the better.

One early one that springs to mind is when MLB changed the rules about ball conditions. Back in the day, pitchers were allowed to modify the ball. They’d spit on it with tobacco phlegm to make it sticky, or rub dirt on it to make it harder to see. At the same time, the game was played with one single ball until it was completely destroyed or the game was over. Thus, by the 9th inning, the baseball was a formless potato that was impossible to throw or hit- or see.

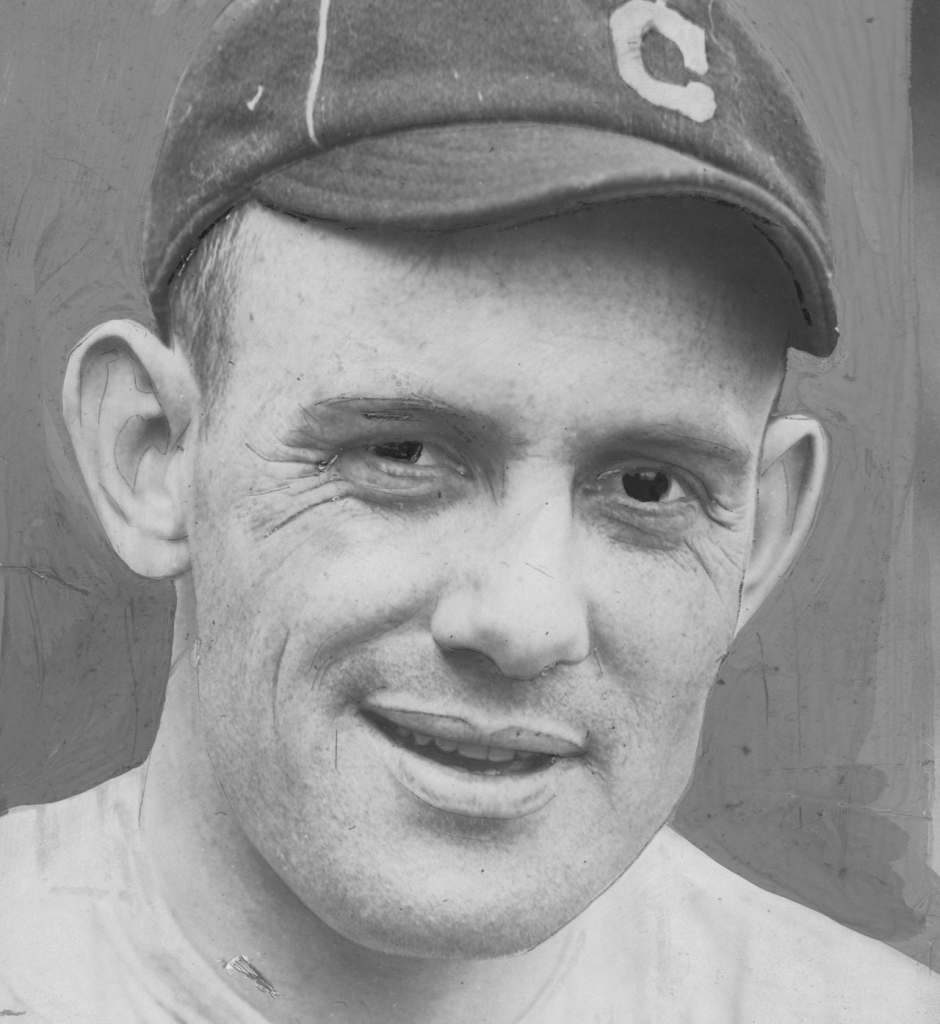

In 1920, Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman took the plate. Yankees pitcher Carl Mays hurled a lumpy black fastball and clocked Chapman right in the head. Chapman went down and died 12 hours later, and remains the only player to suffer a fatal injury on the diamond.

Since then, the rules changed to require umpires to change out the ball whenever it got scuffed or soiled. Spitballs were outlawed later, and batting helmets became a requirement some decades down the line. The Mays-Chapman incident made the game of baseball safer, but had a neat second-order effect- having a clean ball every time makes every pitch fair and even well into the later innings. This leads to more dramatic strikeouts or walk-off homers, and has made the game more exciting.

Another great example is when the league banned steroids in 1991. This was a gradual change because the ban was pretty much symbolic- no testing or consequences were enforced, and you were still fine if you had a “valid” prescription. Drug tests became mandatory in 2003, penalties introduced in 2004, and penalties tightened to the point of meaning anything in 2005. There was so much resistance to this change in baseball that U.S. Congress had to get involved.

I see a lot of nostalgia for the Steroid Era online, with grainy videos of men built like Shrek lobbing dingers out of the atmosphere, but the statistics show that baseball players today are hitting more home runs, pitching faster, and running harder than anybody ever did back then. The game has become more “real,” in a sense.

Today’s article is about one huge change in the game of baseball, one that we still talk about and celebrate today, and was a catalyst in a much bigger and much needed shift in American culture generally. I’m talking about when Jackie Robinson broke the Color Barrier in 1947, being the first black guy to play on a Major League Baseball team.

The standard narrative goes that the Negro Leagues had all the talent but no money. It was pure racism that prevented MLB talent scouts from even checking them out. Then one day, a brave civil rights activist dared peer into the Negro League baseball stats and brought Jackie Robinson up to the majors, ending racism once and for all.

How romantic. Unfortunately, like most things in life, it was all about money- and in the 1940s, one distant country had a ton of money and a newfound love for baseball. This is the story of how Venezuela killed the Negro Leagues.

Viperhawk: Road Rage AVAILABLE NOW!

Space gangsters. Fast cars. An evil interplanetary conspiracy. A sarcastic smuggler who wants nothing to do with any of this.

Viperhawk: Road Rage is a hilarious sci-fi thriller you DON’T want to miss!

The Truth about the Negro Leagues

In 1881, the white owners of the original 8 MLB teams shook hands and made a “gentleman’s agreement” that no black players were to be allowed on their teams.

There was never a written rule on the books about this. Also, this didn’t apply to other minorities for some reason. There were plenty of Latino players in the early days, though they weren’t treated well. The Cleveland Spiders had so many Native American players that they changed their name to the Indians.

Blacks, however, were “forced” into the Negro Leagues, which thanks to racism, had all the talent and no money. That’s the story we’ve all heard, but the truth is that the Negro Leagues were insanely popular. Sure, they didn’t have as much money as the MLB. Most countries don’t have that much money. This doesn’t mean the Negro Leagues were poor , or barely getting by. In the 1930’s and 40’s, the Negro Leagues had a following that rivaled Major League Baseball itself, and they struggled with the same things that big league ball clubs have struggled with forever.

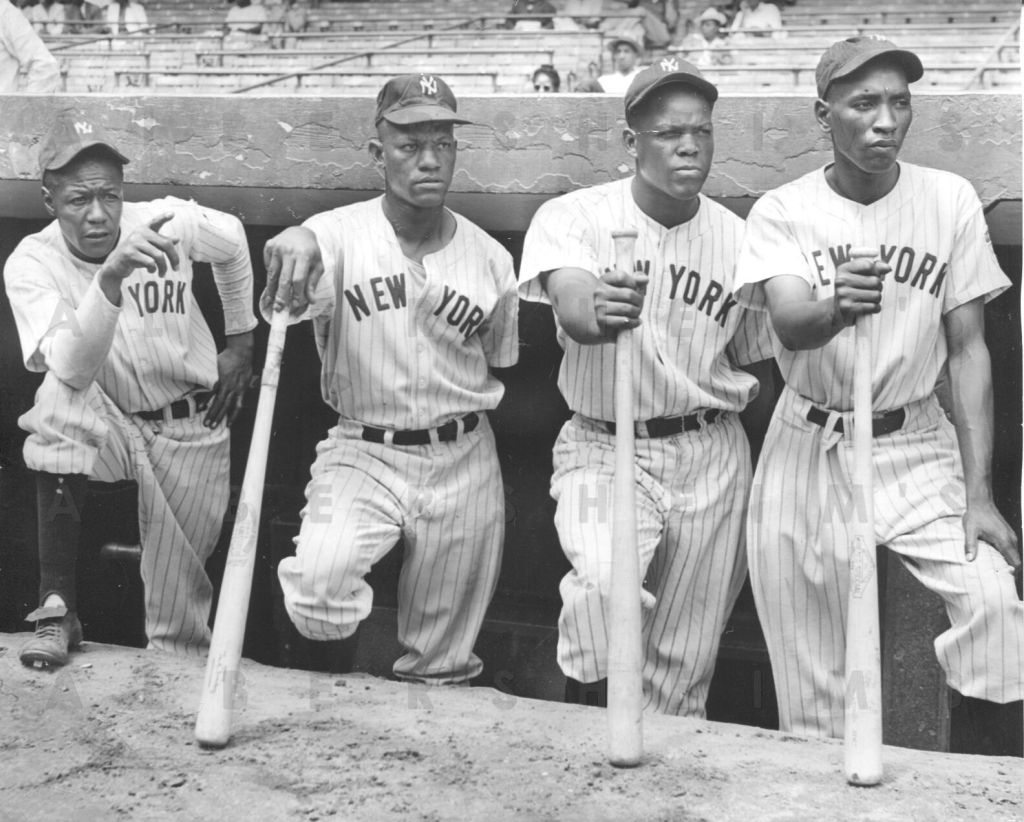

One thing that could make or break a Negro League team was the same thing that can make or break a team now- location, location, location. Every team needs a home base, or the fans don’t have anywhere to go. Take, for instance, the New York Black Yankees. The team began in Harlem but was never able to secure a stadium. They moved around to Queens, to Brooklyn, to Jersey, never able to staple down a home stadium or a dependable a fanbase. They routinely sucked, never breaking out of the bottom half of the league standings.

Most Negro League teams solved this issue by renting stadiums from the MLB. They weren’t allowed on the team, but no gentleman’s agreement barred them from borrowing the stadium when the teams were out of town. This came with drawbacks- many (not all) of these MLB ballparks had segregated bathrooms and water fountains. They didn’t have enough locker rooms to accommodate segregation, so black players had to wear their uniforms to work lot of the time. Still, they had a stable home with the same infrastructure that the MLB had.

It’s easy to paint this as an oppression thing, but stadium sharing is a very practical idea that we still use all the time today. The New York Giants and the New York Jets share a stadium in New Jersey, after all. Most Major League Soccer teams borrow grass from their NFL counterparts. Even in baseball, the transient Athletics are couch surfing in their own Minor League team’s park.

Some teams had enough money to build their own place, like the Pittsburgh Crawfords. They played at Greenlee Field, a venue built and operated by a black millionaire in the 1930s. Greenlee was unsegregated and affordable, bringing in dedicated fans and enough money to give the Crawford top choice in players (incidentally, they were always in the playoffs). The venue hosted dances, boxing matches, exhibition games, and all sorts of fun things. Even more amazing, Greenlee Field was the first professional baseball park to install permanent electric lights, allowing them to host games at night. That was in 1932- the MLB didn’t catch up on that front for three whole years.

Any meathead can figure out that renting a stadium, rather than playing in one you own, is going to drive up operating costs. This was a problem for a lot of Negro League teams, and then the Great Depression came around and hit everyone in the nuts. When income dropped to the point where Negro League teams couldn’t make rent anymore, they couldn’t depend on standard gameplay. The Negro Leagues got creative and started barnstorming– playing fun exhibition games around the country to draw a different kind of crowd.

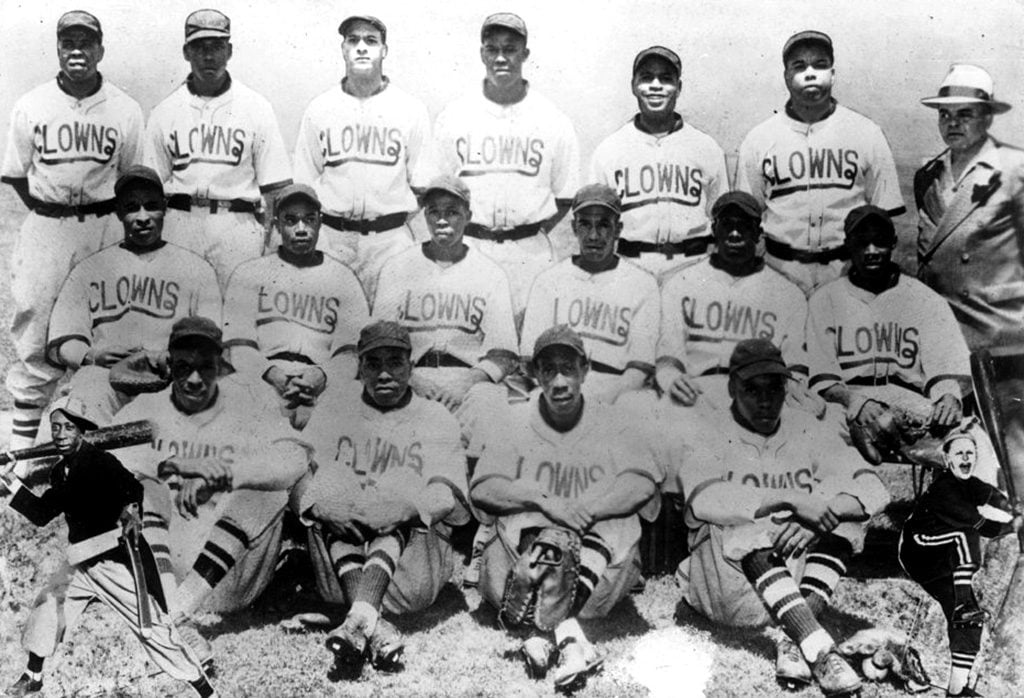

Some of the most popular of these exhibition matches were Negro League versus MLB games. Greenlee Field hosted the Crawfords versus the American League All-Star Team in 1932, the black Crawfords stomping the white AL 11-2. Other teams just starting goofing around, turning baseball into a comedy show, similar to the Harlem Globetrotters or today’s Savannah Bananas. One of these teams was literally called the Indianapolis Clowns.

This new business model meant that the Negro Leagues did well despite the economic nightmare. Exhibition games packed stadiums of 20,000 seats, they played against all-white teams and won, and they were well paid for it. They were good and everyone knew it. It wasn’t the sneering of racists in the MLB that kept blacks out of the Big Leagues, it was tradition.

In the 30s and 40s, Negro League teams figured out that they could make more money by taking their exhibition games on tour. They tried that in the American South, but segregation was even worse down there and the locals were far more hostile than they were in the Midwest.

Then, in the 1940s, a massive economic shift in South America attracted the Negro Leagues’ attention.

Get Spud Content Delivered Right Up Your Butt

Join the email list for updates, new blogs, special deals, and more

The Baseball Boom in Venezuela

In the 1930s, oil was discovered in Venezuela. It was a major breakthrough for a struggling country. Suddenly, foreign investors were shoveling money into South America like it was going out of style. Workers rushed in from all over the Caribbean to pick it up off the floor.

American oil companies invested heavily in Venezuela, and brought with them those hardy American workers. The American drillers made friends with the Latinos coming in for work, and taught them the game of baseball. The oil companies soon started funding local baseball teams and putting on tournaments.

By the 1940s, Venezuela had some disposable income and there was a huge demand for something to do. The government had enough oil money to organize its own professional baseball league. Liga Venezolana de Beisbol Profesional (LVBP) was formed in 1945 with 8 teams, and baseball remains the biggest sport in the country today.

(Editor’s note: The LVBP still has 8 teams in 2025. That may not sound like much, but there’s only 30 million people in the country. Scale it to the size of the USA, and that’s the same has having 80 teams in the MLB. 40 in each league. Nearly triple the baseball per capita.)

Baseball spread across the Caribbean like an oil spill. Venezuela, DR and Cuba didn’t have the same cultural racism that the United States was struggling with, and the ligas were integrated from the get-go. This attracted the attention of the Negro Leagues, who were taking their exhibition matches on the road, and sick to death of being turned away from hotels, ballparks, diners, and toilets.

In 1945, the LVBP invited a team of American All-Stars on an exhibition tour of Venezuela. This team was made up of some of the top Negro Leaguers, including Jackie Robinson himself. They thrashed the Venezuelan and Caribbean teams, and the tour was a huge success. Venezuela organized more of these events, and Negro Leagues started regularly playing matches in South America during the winter.

It wasn’t long before the Venezuelan teams, with their integrated culture and deep pockets, started poaching Negro League players. They bought Sam Jethroe from the Cleveland Buckeyes. They robbed the Indianapolis Clowns of Sam Hairston. Roy Campanella did a season with Sabias de Vargas down there. Martin Dihigo, a Negro League hall of famer, played for and eventually managed Leones de Caracas, the LVBP’s top team.

The United States had competition. The top talent in baseball was becoming the top talent in beisbol. Venezuela was getting all these great players for super cheap. One manager recognized that the only thing keeping the top talent in the game out of his own team was a dumb tradition, an outdated “gentleman’s’ agreement,” and he’d already had his eyes on Jackie Robinson for years.

The Minority Rule

I don’t know about you, but I’ve been hearing some version of the Jackie Robinson folklore since I was in 3rd grade. I don’t need to get into the story here because we’ve all read the books and seen the movies and looked at the murals at Dodger Stadium. Here’s the short version: Branch Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, was an outspoken critic of segregation and wanted to bring the Negro League talent into the MLB for a long time. He finally did that in 1947, when he gave Jackie Robinson the #42 uniform and broke the color barrier.

Rickey was already on a mission towards integration, going against the established culture. He was in the minority, but he had something to believe in. More often than not, those are the people who change traditions.

To illustrate this, think of a family of five. Little Timmy develops a peanut allergy. He’s the only one in the family who has the condition. Timmy, the minority unit, cannot eat peanuts; but the rest of the family can or cannot eat peanuts. Mom isn’t going to cook two separate meals for dinner, that’s too much work- so she’ll make a dinner without peanuts that everyone can eat.

The minority has skin in the game. The majority does not. Thus, the minority unit changes the diet of the whole family. This is called the minority rule. It’s the counter-intuitive way that traditions evolve- by a minority that must have something a certain way, and a majority that can take it or leave it.

Branch Rickey wanted integration. He wasn’t alone, but pro-integration forces in the MLB were few and far between. They were the minority, standing against tradition, with a mission to change things. On the opposite side, there was a minority of those upholding the tradition of segregation, clinging to the familiar. In the middle was the majority; those who might have been swayed slightly to one side or the other, but they just wanted to watch some baseball, dammit! These were the people that would still buy tickets and eat concessions whether blacks play in the Big Leagues or not.

Venezuela’s role in the matter was putting the squeeze on MLB integrationists. The LVBP starting recruiting black players as soon as the 1945 exhibition tour was over. Suddenly, time was a factor. If Branch Rickey had waited any longer to sign Robinson, he might have lost #42 as well. If the integrationists lost all their top talent to Venezuela, they wouldn’t be able to prove their point. Rickey had to put a black man on his team as soon as possible, so he did.

It shattered a long time tradition. It created a lot of noise. It wasn’t easy at first, as the traditionalists fought back, sometimes violently, against such a bold change. Eventually the noise settled and money had the final word. The bulk of baseball fans could take it or leave it, and kept buying baseball tickets. Before long, segregation passed into baseball history.

The floodgates opened and MLB teams started signing black players left and right. Black fans started coming to MLB games, braving segregated seating and facilities to see their favorite black athletes in action. Eventually the Negro Leagues couldn’t afford their own stars and faded into obscurity. The MLB became more popular than ever, between white and black fans alike, to the point where segregating ballparks just didn’t make any sense anymore (by accommodating the minority, they could keep the minority and the majority as customers- minority rule again). Some stadiums in the North, like Wrigley Field and Fenway Park, desegregated before they even signed any black players.

Baseball integrated and the world didn’t end. This strengthened the position of civil rights activists outside of sports, and a broader movement began. The forceful minority made changes, and the majority tolerated it. Step by step the Civil Rights Movement gained ground. Over the next ten to fifteen years, a changing tradition in baseball became a cultural revolution.

It’s all thanks to Venezuela falling in love with baseball.

Stay dangerous my friends ■